Blog of a Blog

Rather than reinvent the wheel for this post, I am re-posting a recent interview shared on the New England Wax blog done by Dietlind Vander Schaaf, who through her astute and insightful questions made this interview a thought provoking exchange.

Dietlind Vander Schaaf: Your work is concerned primarily with capturing and expressing movement—whether of the artist’s bodily gestures, sound vibrations, or that of a spiritual state between death and rebirth. Why is movement so critical to your art?

Kim Bernard: Movement has always been a significant part of my life. I studied dance growing up and continued well into my adult life. I’ve dabbled in African, Latin, Flamenco, even Aerial Silks and Trapeze. When I was just out of art school I studied and eventually taught karate and kung fu. For the last 6 years I’ve practiced Ashtanga yoga. Movement has been a consistent outlet for me.

Back in ’95 my father had a spinal cord injury as a result of a skiing accident. Here’s someone who was very physical… biked, ran, skied, sailed, built. In an instant I saw him become paralyzed from the neck down. Around that time I remember running up stairs because I could, it affected me so deeply. He eventually regained much of his mobility and had a pretty good several years, and then he declined again to the point where he needed assistance with every move and was in constant excruciating pain. Deciding that he just didn’t want to live another 20 or so more years like that, he choose to end his own life. Right around the time of my dad’s accident, we discovered my now 21 year old son had Perthes disease, which meant the femoral head in his left leg was malformed. From age 2 ½ – 5 years old he had to wear a brace by day and a spica cast by night which limited his movement. In 2009 my now 23 year old son, as a result of a football injury, discovered he had been walking around for years with a broken navicular bone in his foot. Again… surgery, casts, pain and limited mobility. Both of my sons are fine now but as you can see, three people that have played such a big role of my life have had significant limitations of movement. I’ve really developed an appreciation that I can move with ease and how movement is not a right, it’s a gift.

Several years ago I assigned myself the task of merging my art making practice with my movement practice. Since then my work has explored movement through kinetic sculpture, mark making, contraptions that make marks and some video.

Dietlind: Your story about your father reminds me of a passage from the book Intimate Death: How the Dying Teach Us How to Live by French psychologist Marie de Hennezel who spent seven years working in a palliative care unit in Paris. In recounting her time working with a patient named Daniele who was paralyzed except for the use of her right index finger, de Hennezel describes a type of survivor knowledge experience:

“When I left Daniele, all I wanted to do was go and run barefoot in the grass like a mad thing. Get drunk on movement! I took my car and went to the park at Sceaux. It was warm, and I realized that the days were getting longer. On the big lawn in front of the castle, I took the most immense pleasure in running in circles, feeling the warm, damp earth under my feet, and I said thank you to life and to Daniele for such a conscious flash of pure joy.”

You describe the merging of your movement background with your art making process as an assignment you gave yourself. I know that meaning and intent play a significant role in your work. Do you always start out with an idea that you want to give form to–and if so, how does form relate to the work’s deeper meaning? Do some ideas naturally want to find themselves realized in 3D versus 2D?

Kim: What a beautiful passage. That quote resonated deeply with me.

I used the word ‘assignment’ but it was really an answer to my own question of why these two realms, my studio practice and my movement practice, were so separate. They were already influencing one another; I just deliberately made them one. It became clear that movement was what I wanted to explore in my work, what I was most curious about and the way I wanted to engage the viewer. I’m always encouraging my students to ‘go deep, rather than broad’. Being intentional about the quest keeps us on track and focused but allows the maker to be open to discovery.

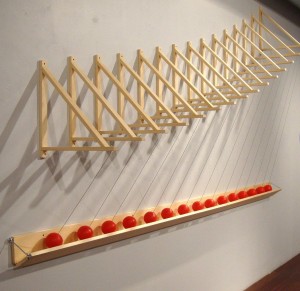

It’s timely that you ask the question about how I start. I have a solo exhibit at Boston Sculptors Gallery (BSG) in May that I’m now generating ideas for. I know the space. I know how I want the viewer to engage and I know the overall Gestalt. It will be interactive and have moving parts you set in motion that leave a trace or a record. There will be a performative element, certainly the work itself or maybe myself. Now I have to figure out the specifics, the materials, the size/s, the palette, the sculptures function and deal with the nuances of design.

In general, as to whether work will be drawn, sculpted, painted, 2-D, 3-D or time based, I try not to impose a medium or method but let the ideas dictate. I do respond to space though. It’s very challenging to conceive of work when I don’t know where it’s going to be installed. Space gives way to ideas and possibilities, especially with 3-D work and certainly with installation.

Barbo State

Dietlind: If the idea and the installation space both inform the dimensions, when does palette come into play? Much of your work is brightly colored—red and black feature prominently. Bardo State is all grey. How is color related to meaning for you?

Kim: Color has great significance and symbolism to me. Color elicits a mood and by thoughtfully selecting a particular color or a palette I believe I can achieve a certain desired effect. For Bardo State I wanted to elicit a somber, reflective, meditative mood so grey was the only color that would work. For Synergy 17 I choose bright orange, an attention getting color that we read as caution, pay attention. Think of traffic cones or construction signs. For Quantum Revival, red for energy, vitality and life was fitting. Using many colors, polychrome, on sculpture presents many challenges. It doesn’t always work so I often use just one color for sculpture. For my 2-D work, where I work in series, I deliberately limit my palette. My most recent body of 2-D work is white, black, red, yellow-gold and green. That’s it. It was a way to create a body of work I knew would hang well together and create unity. I always think of the palette of an exhibit as I’m developing the concept. For my next exhibit at BSG I’m leaning toward white, black, grey and red. That’s a serious and powerful palette.

Dietlind: While tackling complicated or serious subjects, such as physics, your exhibitions are often playful and encourage audience interactivity. Why is it important for you to have viewers break the “no-touch” rule of art and participate in your work?

Kim: While many of us primarily experience stimulus visually, there are many other ways we process information. Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences identifies 8 different modalities through which we experience sensory information: musical–rhythmic, visual–spatial, verbal–linguistic, logical–mathematical, bodily–kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalistic. My own learning-processing style is without a doubt visual–spatial and bodily–kinesthetic. In other words I process information by seeing and doing either with my hands or with my whole body so, of course, I have gravitated to a method of creating that suits me. It seems logical then that in my sculptural work, at least, I aim to expand the viewers experience by offering a hands-on, interactive experience, in addition to the visual and the spatial. It’s all about expanding the experience.

Dietlind: In addition to physics, spirituality is a theme that shows up repeatedly in your work. Projects of yours concern the soul, charkas, Hinduism, Buddhism, Zen—does the work reflect your own personal search for meaning? How so?

Kim: Absolutely. We are all searching for meaning, aren’t we? Sculpture, installation, 2-D work—these are all methods I use to explore what I’m questioning and curious about. Making art is the vehicle through which I learn, connect, communicate, and try to make sense of the world we live in. I don’t pretend to have the answers but I do have plenty of questions.

Dietlind: The cultivation of any artistic practice can take a great deal of time and energy. At times it can be consuming. How do you balance the needs of your practice with the need of your daily life? Does being married to another artist make a difference in terms of meeting those needs?

Kim: It’s definitely consuming, but in a good way. My studio practice is my daily life. It’s not like a 9-5 job that you leave behind at the end of the day. If I’m not creating in my studio, I’m usually involved in some activity that has to do with my work. I may be planning, researching, documenting, picking up supplies, delivering work, teaching, etc. If I’m not doing, I’m often thinking. I do a lot of that while driving. I try to keep a balance in my life by practicing yoga, reading, spending time with friends and family and traveling whenever I can.

Being married to an artist helps in that Christos ‘gets it’. He understands the creative process, the complexity of being a full time artist, the all-consuming nature of it and the unpredictability because he works at his painting full time too. The drawback to both being artists is that neither of us can lean on the other financially. We each have to pull our own weight. What’s great is that we share the same interests and understand one another. We look at one another’s work, offer feedback, and support one another completely. That’s invaluable to me. I wouldn’t want it any other way.

Comments

Post a Comment